X-ray Studies at SLAC and Berkeley Lab Aid Search for Ebola Cure

Research Reveals Structures That Could Be Key to Preventing Infection

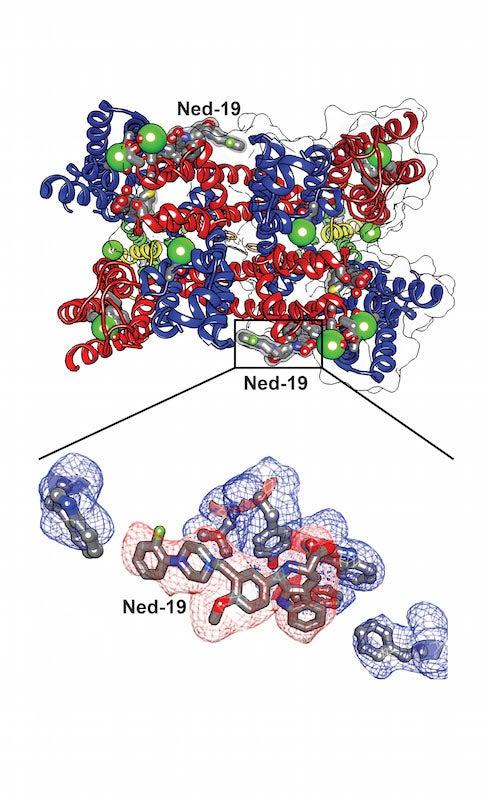

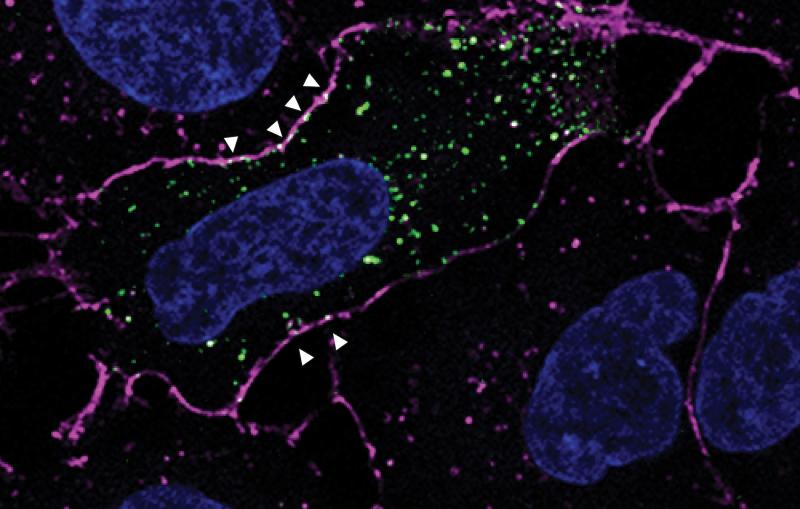

In experiments carried out partly at the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, scientists have determined in atomic detail how a potential drug molecule fits into and blocks a channel in cell membranes that Ebola and related “filoviruses” need to infect victims’ cells.

The study by researchers at University of California, San Francisco marks an important step toward finding a cure for Ebola and other diseases that depend on the channel. The results were published March 9 in Nature.

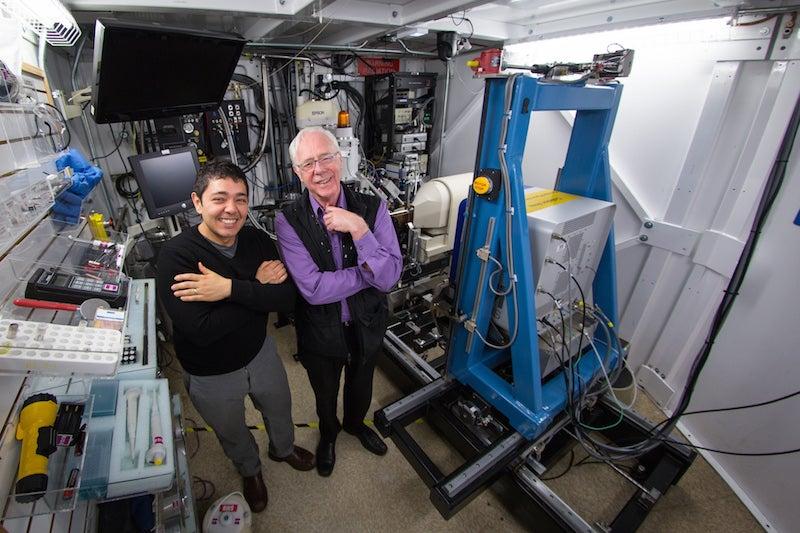

“There are no effective treatments for filovirus infections in humans,” said UCSF postdoctoral researcher Alex Kintzer, who performed the study with Professor Robert Stroud. “With these new structures, pharmaceutical chemists can now design new candidate drug molecules that would be more efficient and effective in blocking the channel and defeating these viruses.”

To determine the structures, Kintzer first made crystals containing many copies of the target channel protein, called TPC1, bound to the potential drug molecule, Ned-19.

The researchers then exposed the crystals to intense X-rays at two DOE Office of Science User Facilities – SLAC’s Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) and the Advanced Light Source (ALS) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Analyzing the patterns and intensities of the X-rays that diffract from the crystals enables researchers to determine their atomic structures.

Isolating TPC1 from its complex membrane structure is a difficult process that often results in loosely packed crystals that produce faint diffraction patterns, and finding crystals that diffracted well enough to determine the atomic structure of TPC1 required extensive analysis. SSRL’s Beam Line 12-2 was crucial to the successful analysis of these crystals, because its bright X-rays are particularly well-suited for biomedical diffraction studies, and its pixel-array detector is 1,000 times faster than conventional detectors in logging data.

“These features of Beam Line 12-2 were especially important in enabling Alex to rapidly analyze the diffraction of his challenging crystals,” said Ana Gonzalez, SSRL’s Macromolecular Crystallography User Support Group leader, who helped Kintzer take full advantage of the beamline’s capabilities.

Even so, the project involved testing about 6,900 crystals during more than 36 sessions at SSRL and ALS. It took nearly four years to complete, from planning to publication.

One interesting aspect of this study is that the specific TPC1 sample the researchers used did not come from a human or lab animal. Rather, it was from the cells of a weedy Eurasian annual plant related to broccoli (called mouse-ear cress, or Arabidopsis thaliana) that researchers have used as a model species for studying cell activities and genetics since the mid-1940s. (In 2000, for example, A. thaliana’s genome was the very first plant genome to be sequenced.)

“It’s common in this field to use well-studied non-human components that have similar genetic sequences, structures and functional properties,” Kintzer said.

Future research plans include determining the structure of human TPC1 and investigating other molecules that may treat or cure other diseases that exploit that channel’s function.

“For example, TPC1 function also plays important roles in the progression of diabetes, obesity, fatty liver disease, heart disease and such neurodegenerative disorders as Parkinson’s disease,” Kintzer said. “We hope our work will eventually lead to more effective medicines for treating these diseases as well.”

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Sandler Foundation. Funding for the SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is provided by the DOE Office of Science and the NIH National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS). The Berkeley Center for Structural Biology is supported by NIGMS and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Citation: A. Kintzer and R. Stroud, Nature, 9 March 2016 (10.1038/nature17194).

Contact

For questions or comments, contact the SLAC Office of Communications at communications@slac.stanford.edu.

SLAC is a multi-program laboratory exploring frontier questions in photon science, astrophysics, particle physics and accelerator research. Located in Menlo Park, Calif., SLAC is operated by Stanford University for the U.S. Department of Energy's Office of Science.

SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory is supported by the Office of Science of the U.S. Department of Energy. The Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.